Elk Hunting and the General Rifle Season

One October many moons ago in Colorado, I thought I had it figured out. I drove out to my hunting area two days before the general rifle season opened and there wasn’t another soul in sight. I joyously set up camp and then scouted on foot both days, locating two small herds of elk. Man, I thought, this is great!

The afternoon before the opener, the other hunters started arriving in droves. Where did they all come from? The dirt road leading to camp looking like an L.A. freeway during rush hour. Rats, I remember thinking. Now what?

Obviously, I needed a new game plan, and one completely different from hunting the rut.

Scout As You Go

Most general firearms elk seasons do not open until the rut is, for all intents and purposes, over. While elk still talk upon occasion, where the mountains rang with raucous elk bugling just a few weeks before, now all that can be heard are tumbling streams and screaming mountain jays.

Elk are herd animals that live in small, isolated pockets in a vast sea of good-looking habitat. A large elk drainage may encompass 50 square miles, but elk may be living only in a handful of places in that entire drainage. To kill a bull, you have to first find one—and you can’t find one unless you cover some country. This point cannot be overemphasized.

Be sure your rifle is sighted in properly and that you can consistently place your bullet at the ranges you expect to be shooting.

Our hypothetical 50-square mile drainage may be 10 miles long and five miles wide. It may also encompass a lot of country between the valley floor and the tallest peaks several thousand feet higher, with lots of finger drainages branching off the main drainage. At first, the task seems impossible: How do you hunt this entire place in a week’s hunt?

The answer is, you don’t. You scout on the go, splitting up the drainage into manageable sections with your hunting partners. Your first goal isn’t necessarily to kill an elk, rather simply find elk to hunt.

Three or four hunters in decent physical shape, who know how to climb high and glass early and late and able to walk five to 10 miles during midday searching for elk sign, can cover the entire drainage in two or three days. This kind of teamwork is crucial if you did not have a chance to scout before season, as most nonresident hunters do not. It’s imperative you find the elk—and the other hunters.

Post-Rut Bulls

After rutting, bull elk, especially the old herd bulls, are tired and worn out. They’ve expended huge amounts of energy breeding and protecting their harems from interloping satellite bulls. Your scouting efforts may produce lots of elk, but they will more than likely be cows, calves and small- to medium-sized bulls. That’s because herd bulls post-rut are ready to resume their life of bachelorhood. They often find isolated pockets of deep cover where they can rest without being disturbed by anybody or anything, including other elk. This they do either alone or in small groups of other bulls.

You can find these pockets in the dark timber, among blowdowns and other hell-hole cover, on small benches notched into the sides of steep, brushy ridges, near high-mountain saddles, in thick creek and river bottoms and other nasty, inhospitable places. Remember, too, that while elk like to bed in the same general area day after day, they won’t necessarily bed in exactly the same place day in and day out. So, before moving in on them, it is always better to try and spot them first with your optics.

While bugling makes no sense during the general rifle season, the judicious use of a cow call can help locate elk in the deep timber.

(A quick footnote. Reports from many friends who have hunted areas in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming for many years, areas that are now covered up with wolves, tell me that the elk in these areas have started living in the nastiest, meanest country in the region as they try and escape fang and claw. Those friends have had to shift their hunting tactics accordingly.)

Plan Carefully

Once you’ve found the elk, you must plan carefully before making your move. If you spook them with your scent, careless walking and talking or poor shooting, chances are they’ll move several miles and you’ll have to start all over again.

When approaching elk, make sure all parties use caution. Never underestimate an elk’s eyesight, especially its ability to spot a careless hunter out in the open with the sun shining on him. Try and move in from either the same elevation as the elk or, ideally, a bit above them.

If you’re trying a drive—and small drives can work well, especially if you’ve scouted the area and found places that make natural funnels for escaping elk—place the standers to cover these escape routes and, if you have enough people, a stander to cover any back-door escapees. The drivers should actually be still-hunters doing their best to slip up on the herd and get their own shot.

Outsmart the Hunters, Outsmart the Elk

On my Colorado hunt, instead of giving up, I did what I love to do when there are lots of other guys around: Let the other hunters work for, not against, me.

On opening morning, I grudgingly crawled out of my sleeping bag at 2:00 a.m., grabbed my rifle and pack, and quietly started up the mountain in the dark. I kept a low profile, careful not to let the other camps see or hear me. It took three hours of hard climbing, but by 5:30 a.m. I was set up in a saddle 2,500 feet above the valley floor. My perch overlooked two long, deep, timbered canyons, both of which had well-used elk trails coming out of the top of the timber stringers that led into my saddle. I had stumbled across this spot during my scouting, and it was obvious that here was a natural pathway for the elk to travel between one drainage and the next.

A great tactic when other hunters are running around is to climb high in the dark, get comfortable in a known travel corridor and let the other hunters push the elk to you.

I found an old log to lie behind, over which I first set my day pack, then rested my rifle. I took a long drink of water, dug my binocular out and got ready. An hour or so before daylight, the sounds of waking hunters traveled up the slope—it always amazes me how far sound travels in the mountains. As soon as it got gray enough to see, I spotted my first elk in small open pockets about halfway down the slope. Far below, I could soon see several orange vests working their way through the brush. I was reminded of the massed charges infantrymen made on entrenched positions during the Civil War and, like the hunters below, how futile their efforts usually were.

During the first 30 minutes of light I saw no less than 75 elk, mostly cows and calves, as they worked their way up and across the slope, with several passing through my saddle into the safety of the next drainage. Then, out of nowhere, a very nice, heavy-antlered 5×5 bull led a small procession of six elk into the saddle at a trot. The 75-yard shot was a gimme.

Rocket Science? I Don’t Think So!

The same scenario has played itself over for me many other times in similar fashion, and turning a problem into success isn’t rocket science. That morning I had two choices, beat my head against a big rock and hunt with the masses—with minuscule odds for success—or let the other hunters do the work for me, in essence becoming a large herd of beaters driving the elk right past my hide.

The general rifle season is a tough time to kill a bull, but it can be done. Just ask this smiling hunter!

The key is to recognize the opportunity when it arises and, through scouting and/or knowledge of the terrain, determine where the elk are likely to move once they’re spooked and begin to escape to greener pastures. Whenever possible, it’s advantageous to set up above the elk and the other hunters and to play the wind. It’s always helpful if nobody sees you take your stand.

Who says you have to join the crowd? I’d rather beat ’em instead by letting them do the hard work. Best of all, the meat pack-out was all downhill!

*-*-*-*-*-

Bob Robb is one of the most well-respected voices in outdoor media, with more than 40 years of columns and essays in print recounting his exploits in the field. A renowned archery expert, Robb has hunted on five continents and also lived 15 years in Alaska, where he held an assistant hunting guide’s license. His work has appeared in titles small and large, from American Hunter and American Rifleman to Whitetail Journal, Field & Stream, Petersen’s Hunting, Deer & Deer Hunting, and many others. He recently retired as Editorial Director from Grand View Media Group, where he oversaw the content for eight publications, including Bowhunting World, Predator Xtreme and Waterfowl & Retriever. Still, retirement is rather an ugly word to Robb, and so he continues to contribute to a variety of publications, just as he continues to hunt around the world.

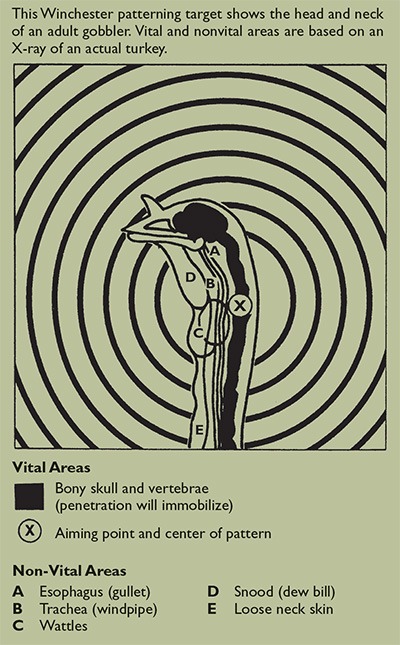

Turkeys make a tough target. They are difficult to see and even harder to harvest. The head and neck are the only vital areas that ensure a fast, clean hunt, but this will only happen if your shotgun throws a tight, dense shot pattern.

The best shotgun choice for turkeys is a 12-gauge magnum, though the 10 gauge is gaining some ground among turkey hunters. The best shot sizes are No. 2, 4, 5, or 6. The best shotgun chokes are Full, Extra Full, and Super Full.

Turkeys make a tough target. They are difficult to see and even harder to harvest. The head and neck are the only vital areas that ensure a fast, clean hunt, but this will only happen if your shotgun throws a tight, dense shot pattern.

The best shotgun choice for turkeys is a 12-gauge magnum, though the 10 gauge is gaining some ground among turkey hunters. The best shot sizes are No. 2, 4, 5, or 6. The best shotgun chokes are Full, Extra Full, and Super Full.

1. Public Lands and Wildlife Management Areas: One of the best and most accessible options for hunting collared doves ethically is on public lands and wildlife management areas. These areas are often managed by state or federal agencies, and hunting regulations are strictly enforced to ensure sustainable practices.

1. Public Lands and Wildlife Management Areas: One of the best and most accessible options for hunting collared doves ethically is on public lands and wildlife management areas. These areas are often managed by state or federal agencies, and hunting regulations are strictly enforced to ensure sustainable practices.