Hunting High-Country Mule Deer

By Bob Robb

It had been a long, long week. I’d backpacked several miles into the high country of southwestern Colorado, lived on military-surplus freeze-dried something and creek water, and blistered both my heels. A midweek thunderstorm and nearly destroyed my little tube-tent shelter, and my nose was beet-red from sunburn. And yet, I was having a blast! I was hunting early season mule deer on their summer range, and my only company had been chattering marmots, squawking jays and the deer.

A backpacker since the late 1960s—you younger-generation folks should have seen the bulky, heavy, archaic gear we had back then—I discovered early in life that mountain mule deer are best hunted during two periods. The first is the late-season rut and/or migration, if you can obtain a tag. The second is the early season, when bachelor groups of bucks roam above the timberline.

There are many reasons to love early season hunting during August and September. The days are long and the countryside filled with lush grasses and wildflowers. Mountain weather is finicky regardless the season, but while thunderstorms and temperature drops should be expected and planned for, the days of the early season are generally mild and the nights crisp without the bone-numbing cold of the late season.

Hunting alpine mule deer is, without question, one of North America’s toughest hunting challenges.

Bucks are still grouped up and will be until roughly the end of September and early October when they drop down into the timber and become pretty hard to find until much later in the year. You find them by covering a lot of ground with your feet, but most of your searching will be done with your optics, peering into verdant bowls, canyons spotted with timber and sagebrush flats at dawn and dusk as the deer feed heavily, trying to put on maximum poundage to survive the rigors of both the rut and winter.

Topography, Glass Time and the Pocket Principal

The small bachelor groups of early season are usually made up of bucks of the same age class or within a year or two of each other. It is the hunter’s job to locate those pockets that hold the bucks—and in the high country, deer are not around every corner nor in every lush bowl.

I’ve written about the “pocket principal” for decades, a phrase I use to describe those isolated mountain sections that hold deer at any given time. All high-country mule deer live all summer long in isolated pockets, but that with decades of experience backing me, I can tell you that the “pocket principal” says 95 percent of good mule deer habitat holds no deer at all.

Today, it’s relatively easy for hunters to locate potential pockets—this can be one alpine bowl and a single patch of timber for cover and security or, more likely, two or three adjacent bowls connected by saddles or strips of dark timber—before leaving the house. Satellite imagery like that from Google Earth and MyTopo.com, as well as popular phone apps like OnXmaps, ScoutLook, HuntStand, Powderhook and others, provide the goods.

This kind of pre-hunt planning also lets you create a timeline for your hunting week that goes something like this:

- Day 1, backpack into the high country and set up camp.

- Day 2, check out two good-looking bowls to the north.

- Day 3, check out two other bowls to the west.

And so on.

Checking out these potential bowls involves getting into position before daylight, setting up a glassing station and carefully picking apart the area looking for deer: this is careful, slow glassing, evaluating the area over and over as cloud cover shifts and light changes. Midday, you should likely plan to hike around the area, looking for the usual fresh deer sign—tracks, droppings, old beds and so on—taking care not to skyline yourself and keeping your scent from drifting down into the dark timber where unseen deer may be bedded.

Despite the weight and bulk, 15×56 binoculars like this Swarovski 15×56 W B mounted on a tripod are worth their weight in gold for all-day glassing sessions.

Some habitat is better than others, of course. The north- and east-facing slopes get the most shade, so they have the most moisture and, thus, usually the highest-quality browse, so begin searching there. Look, too, for streams and small creeks, strings of timber that provide cover for deer to move back and forth between bowls and tall, vertical cliffs and rock faces that provide safety from predators.

One backpack hunt I made with a friend many years ago went something like this. We had hiked 10 to 15 miles a day for nearly two weeks and glassed several good-looking bowls. During that time, we found four pockets of mule deer bucks.

After a time, we could almost predict where they’d be every morning and afternoon. Some days, one bunch would be in alpine bowl “A,” feeding happily along. The next day, that same bunch would have moved through a saddle to bowl “B.” The next day, they might be in bowl “C.” The next day, they were back in bowl “A,” all in about two square miles. (Decades of experience tells me they make these kinds of relocations to keep from over-browsing a specific bowl.) We hunted an area around them of about 10 square miles and never found another bunch of bucks (remember what I said about the “pocket principal”).

If you don’t see any deer after a couple days, pack up camp and move five miles or more to another area your maps indicate have all the necessary ingredients. There you’ll start the process over again. Sooner or later, you’ll find the deer. When you do, it’s time to begin hunting them in earnest.

Shooting from improvised field positions is standard procedure on backpack hunts, and a backpack makes an excellent rest when shooting prone.

Sneak-and-Peek

One of the most effective ways to hunt early season muleys in the high country is what I call “sneak-and-peek” hunting. It’s something I do when my glassing hasn’t turned up anything exciting and I want to find another location from which to glass. As soon as the morning thermals begin rising and carrying my scent upwards, I like to move along high finger ridges that, ideally, border some lush feeding meadows. At the upper edge of these meadows, you’ll often find large rock outcroppings, small patches of timber, etc.—ideal bedding areas. I silently move along the backside of the ridge for a ways, then carefully sneak to the top by crawling. There I carefully peek over the edge and look for deer. You can glass distant areas from these vantages, of course, but I’ve often found deer directly below me, many times within spitting distance.

Guns, Loads and Optics

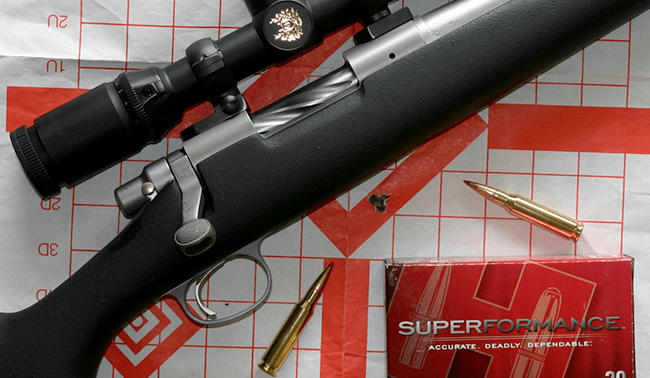

High-country hunting is for lightweight mountain rifles chambered in cartridges from the .243 up through the .300 magnums. Shots can range from in-your-face to way-out-there across wide canyons, so precision is a must.

Lightweight mountain rifles like this Remington KS Mountain model chambered in 7mm-08 Rem. are easy to backpack into the high country and offer the accuracy required.

Riflescopes in the 2.5-10X, 4-16X and even 5-25X are sound choices. Many serious mountain hunters today use scopes with ballistic turrets combined with a laser rangefinder to help with precision bullet placement at extended ranges.

A lightweight tripod upon which a binocular can be mounted will improve your ability to find deer tenfold over using a hand-held binocular. I suck up the extra weight and pack my Swarovski 15×56 W B bino, which weighs about 3½ pouds, but these and similar high-quality 15X binoculars are the ultimate all-day glassing tool.

Let’s Go Hunting!

High-country mule deer hunting isn’t everybody’s cup of tea. Admittedly, you need to be in pretty good physical condition to take on the rugged peaks for a week or more. (And I don’t like heading into the back country for any less than a week. Every time I do, it seems as if, about the time I’m finally into the deer, it’s time to go home.)

Despite the hard work and living in a tiny tent eating crappy food, for me the high alpine meadows of mule deer country in late August and early September are worth the price. When you glass-up a bachelor herd of mature bucks with no other hunters in sight and a week ahead of you, you’ll count your lucky stars and believe it’s worth it, too.