Back-Country Hunt Survival

The key to backcountry survival is avoiding trouble in the first place. However, as one of my hunting buddies is fond of saying, “In hunting, anything that can go wrong will go wrong—and then something else will go wrong.” The more time you spend in the backcountry, the chances of needing survival gear and the skills to use it increases proportionately. Will you be ready to meet the challenge when it happens to you?

Common-Sense Precautions

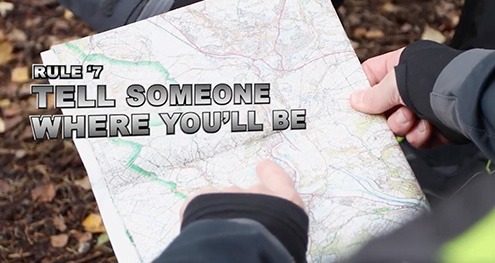

Never, ever go hunting without telling someone where you’ll be going and when you expect to return. That’s as true for a half-day’s sit on a whitetail stand as it is for a week’s backpack hunt.

Know the country in which you’ll be traveling. On backcountry trips, carry topographic maps and a compass, and know how to use them. A GPS unit is great, but you best be ready if it fails; Google maps won’t do you much good without cell reception.

It is critical you know your hunting area’s weather extremes, especially if you’ll be a long way from roads, your vehicle and cell phone range. Historically, what are the worst conditions you can expect? Be prepared to handle them with that extra layer for warmth or a packable rain suit to stay dry.

Naturally, the gear you pack depends on where you’re hunting and how long you expect to be gone. For extended backcountry hunts, always pack basic survival gear (more on that below), customized to your needs. And whether you’re hunting just for the morning a mile from home or miles into true wilderness, if you have not taken a certified first aid course, do so. A call to the Red Cross, your local community college and fire and police departments can help you find a class in your area. The knowledge gleaned from a short, one-day first aid class can literally save your life or that of your companions.

STOP: Count the “Rules of Threes”

Survival instructors teach you that the first thing to do when something goes wrong, whether it be an injury or being lost, is to STOP, the acronym for Stop, Think, Observe and Plan. Sit down and think the situation through. Remember the “Rules of Three:”

- You may be doomed in three seconds if you let panic rule

- You cannot live more than three minutes without oxygen.

- You cannot live much more than three hours in extreme temperatures without body shelter (warmth)

- You cannot live much more than three days without water

- You can live up to three weeks without food.

With this in mind, prioritize your next moves in a calm, orderly and controlled manner. Build your course of action around the following steps:

- Choose a well-sheltered camp site, preferably near water and fuel for a fire

- Set up a system of signals with back-ups (cell and satellite phones, mirrors, flares, personal location beacons, etc.)

- Build a shelter, if you have sufficient strength and materials handy, without wasting valuable energy.

- Gather firewood and water.

- Maintain a positive attitude, dispel your fears, and boost the will to live. That’s not a platitude, this is the mental stuff that will get you through a difficult situation.

Survival Kits

I never, ever head afield without basic survival gear. That’s true whether I’m traveling by foot, horseback, boat, vehicle or airplane. Regardless the size or type of survival kit you carry (I have several, depending on the trip, time of year, terrain and mode of transportation), it must be able to help you do the following:

- Carry out basic first aid chores.

- Build a fire, using two different techniques. This will be your choice, but waterproof matches or regular matches in a waterproof case, plus a butane lighter usually take care of this.

- Construct a shelter.

- ignal for help.

- Purify water.

My kit also contains spare prescription eyeglasses, a compass with mirror and a small wallet-sized survival guide. In addition to basic survival clothing items, in my day pack you will always find the following items:

- Space blanket.

- Compact space bag that can serve as an emergency sleeping bag

- 50 feet of nylon parachute cord.

- A multi-tool.

- Hunting knife. Another once that’s a personal choice, but a folder takes up less space. Whatever you choose, make sure it’s sharp.

- Half-roll of black electrician’s tape.

- One new butane lighter and one “light anywhere” butane survival lighter.

- Fire-starter materials.

- Half-roll of fluorescent orange flagging.

- Water purification tablets.

- One plastic, wide-mouth, quart-size water bottle with screw top.

- A small wire saw, with which you can cut poles for rigging a lean-to.

- Small squares of aluminum foil for melting snow.

I also like to carry a couple of very large, extra-heavy plastic garbage bags both for storing stuff out of the elements and for use as a crude shelter if need be.

Basic First Aid Kits

First aid kits should personalized for your needs and include a few spare prescription pills. In addition, in mine, I carry:

- A half-roll of 1-inch cloth athletic tape. An Ace bandage and even a roll of vet wrap can come in handy too.

- Small tube of antibiotic ointment.

- Assorted Band-Aids.

- Roll of mesh gauze.

- Small roll of antacid tablets.

- Ibuprofen tablets.

- Small bottle of eye drops.

- Lip balm.

- Prescription pain pills.

- Suture materials and a small tube of Super Glue. Believe it or not, you can stop reasonably serious bleeding by gluing deep cuts together rather than stitching them up.

A tourniquet can also be a valuable addition to your kit.

Shelters Basics

The secret to life is staying dry and warm, an important consideration even in temperate climates and good weather. That means staying out of the elements. Building an emergency lean-to type shelter and fire is paramount to this.

Your space blanket, rigged with your parachute cord and some poles as a crude lean-to, can keep the wind, rain, and snow off. The silver side of the blanket should be toward you, so it can reflect warmth from your fire back onto your body.

Remember that you can use literally anything and everything Mother Nature provides to build your shelter, including blown-down trees, chunks of sod and mud, rocks, overhanging rocks or small caves and even snow. On winter hunts, one shelter type I use even in midday when I’m cold and miserable it to dig the snow out from around the base of a conifer tree having limbs that hang down to the snow level, trim all the dry inside branches away both for comfort and tinder, and line the bottom of the shelter with green limbs. It can get quite cozy.

Hypothermia is your worst enemy, and it doesn’t have to be below freezing for this killer to grab you. Statistics show that more people die from hypothermia in temperatures ranging from the low 40s to mid-50s (Fahrenheit) than any other. If it looks like you’re going to be there a while, even overnight, creating a crude shelter from wind, rain, and snow is important.

The four ways to avoid hypothermia include staying dry, staying out of the wind (thus avoiding wind chill), understanding the cold and never ignoring shivering, which indicates that you could be on the edge of hypothermia.

Another “gotcha” in cold weather is frostbite, which is the freezing of body parts. It is a constant danger in freezing and sub-freezing weather, especially where strong winds are blowing. The first sign of frostbite is numbness, not pain, and a grayish-yellow or whiteness to exposed skin. It is important to get potential frostbite victims into shelter and near heat as soon as possible, warming the affected parts with warm (not hot) water until soft, even if this hurts (it probably will.) Body heat, commercial chemical heat packs and extra clothing and blankets can be used to help treat frostbite.

Backpacking into remote wilderness areas means you’ll have to take care of any problems that arise by yourself, including medical issues.

Signaling for Help

Communication devices are prevalent in the woods today. Cell phones are great, but they don’t work everywhere. Satellite phones are actually readily available and much better than a cell phone, and there are rental plans available at reasonable costs. If you spend significant time hunting alone, especially in remote areas where cell phone reception is nonexistent, a satellite phone is something worth looking into.

Other signaling tools to consider include the mirror on your compass, a properly shrill and loud signal whistle, a flashlight (always handy on a hunt anyway) and flares. If you’re waayyy out there, a personal location beacon device—formally called an Emergency Position Indicator Radio—could literally be a life-saver.

*-*-*-*-*-

Bob Robb is one of the most well-respected voices in outdoor media, with more than 40 years of columns and essays in print recounting his exploits in the field. A renowned archery expert, Robb has hunted on five continents and also lived 15 years in Alaska, where he held an assistant hunting guide’s license. His work has appeared in titles small and large, from American Hunter and American Rifleman to Whitetail Journal, Field & Stream, Petersen’s Hunting, Deer & Deer Hunting, and many others. He recently retired as Editorial Director from Grand View Media Group, where he oversaw the content for eight publications, including Bowhunting World, Predator Xtreme and Waterfowl & Retriever. Still, retirement is rather an ugly word to Robb, and so he continues to contribute to a variety of publications, just as he continues to hunt around the world.

Excise taxes fund wildlife research for the sustainable maintenance of healthy wildlife populations.[/caption]

The excise taxes established under the Pittman-Robertson Act have been a driving force, contributing over $16.4 billion (over $25 billion adjusted for inflation) to individual states. In this video, Peter Novotny, Deputy Chief of the Ohio Division of Wildlife, highlights how these funds, combined with hunting and fishing license dollars, fund essential wildlife research. This research enables a deeper understanding of how wildlife populations adapt to a changing environment, ultimately leading to the maintenance of healthy and sustainable populations.

Excise taxes fund wildlife research for the sustainable maintenance of healthy wildlife populations.[/caption]

The excise taxes established under the Pittman-Robertson Act have been a driving force, contributing over $16.4 billion (over $25 billion adjusted for inflation) to individual states. In this video, Peter Novotny, Deputy Chief of the Ohio Division of Wildlife, highlights how these funds, combined with hunting and fishing license dollars, fund essential wildlife research. This research enables a deeper understanding of how wildlife populations adapt to a changing environment, ultimately leading to the maintenance of healthy and sustainable populations.

“We feel comfortable and confident that the excise tax dollars are helping keep healthy deer herds out there across the United States,” said Phil Bednar, President and CEO of TenPoint Crossbows.[/caption]

“We feel comfortable and confident that the excise tax dollars are helping keep healthy deer herds out there across the United States,” said Phil Bednar, President and CEO of TenPoint Crossbows.[/caption]